Komechakartgallery

Articles on the art found at Benedictine University and the Fr. Michael E. Komechak, O.S.B. Art Gallery, Lisle, IL . USA

Saturday, February 13, 2021

Missing Museums: Why Art is a Necessity for Public Health by Veronica Esposito

The following article I found while browsing the news. I thought it would be a good read while we ponder those things that are held dear - namely art and going to a museum.

Standing before Jay Defeo’s Incision—some 500 pounds of cracking, granite-like paint whose ten feet towered over me like a majestic, mute mystery—I felt absorbed by something so much grander than anything I had seen in months. I felt transfixed and transported, calmed and enlivened. I felt connected. These feelings grew to encompass my entire body, and right at that moment I realized something important. I had been missing art. I had been missing it very, very much. I hadn’t known it until just then, but I’d been sorely lacking exactly what Incision was giving to me. Because of COVID, because of the physical impossibility it imposed against standing in a museum to become absorbed in a work of art, my body hadn’t known this experience for at least a year. And now I was back, taking drink after bountiful drink from this oasis.

I was acutely aware of these things on the afternoon that I visited the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Having my privilege of being inside a museum revoked—and then, very briefly, returned—had swept away enough of the mental sediment that had collected around my experience of art to make the whole museum visit feel new and unfamiliar. It felt enlivening and restorative, calming and stimulating, joyous and communal. I felt calm and at peace in a way I hadn’t in ages, and I could feel the pleasure of everyone around me, even though all were wearing masks and I couldn’t see their undoubtedly pleased facial expressions.

It perhaps says something about what we value as a culture that during COVID we have seen protests inside of malls and supermarkets, we have seen lawsuits over a person’s right to worship in church and to eat in a restaurant, but we have not seen outcries over an individual’s right to visit a museum. Perhaps this is indicative of the fact that, just as art is construed as a luxury of the monetary and cultural elites—a luxury that may quickly and painlessly be jettisoned once crisis circumstances erupt into daily life—our temples of art are also seen as disposable in the face of more practical necessities. Currently in the State of California, I can purchase clothes, gadgets, and fast food within an indoor mall, but I cannot experience art inside of an indoor museum.

I find it unsettling to now know that individuals will show up to fight for their right to worship in person or to consume a hamburger in a restaurant or to shop for groceries without wearing a mask, but they will not raise an outcry over the art that has vanished from their lives. No one seems to have informed these individuals that scientific studies have demonstrated the great importance of museums to the health of our communities. Such studies have also linked the practice of visiting an art museum to a surprisingly diverse range of health benefits, some of which are: reduced stress, improved memory, relief from chronic pain, improvement in the outcomes of psychotherapy, a longer lifespan, increased vitality, a substantial and rapid decline in the stress hormone cortisol, decreased mortality from cancer, cognitive enhancement in individuals with dementia, and improved immune system function.

I do contend that the ability to enjoy art in-person, inside of a museum setting, is a very significant thing to lose. Beyond the practical, measurable benefits of art museums, science has also attempted to describe what is much less tangible: the unique sense of connection and well-being, of softening vision and falling into depths, of emotional plenty and mental engagement that one experiences while standing before an entrancing canvas. One study—titled “Move me, astonish me . . . delight my eyes and brain: The Vienna Integrated Model of top-down and bottom-up processes in Art Perception (VIMAP) and corresponding affective, evaluative, and neurophysiological correlates”—declares that:

Understanding this multifaceted “power” of art to affect viewers stands as a key pursuit for psychology. . . . [A]rt viewing is notable for its unique blending of bottom-up processing of artwork features (form, attractiveness) with top-down contributions of memory, personality, and context. These are further united with even higher-order, complex, and often effortful cognitions whereby we respond to our initial reactions, discover complex meanings, novelty, and make judgments. This also touches particularly profound reactions that are often recorded in belletristic accounts by art writers or museum visitors that sit at the fundament of psychology itself. Viewers recount powerful moments of awe, pleasure, insight, transformation, deep veneration, or anger to the point that art is even attacked. Art also delivers states of harmony, thrills, chills, tears, or compelling mixtures of reactions such as pleasure from negative or disgusting images, or, say, happiness with “sad” art.

This description of art makes me reflect that one would be hard-pressed to imagine any other single experience that could give rise to such a panoply of conflicting, overpowering, and complex reactions. If the VIMAP is correct, art grants us access to an immensely rich, complicated range of emotion and cognition, while also causing us to experience a sense of expansiveness regardless of if the art work is one of Jackson Pollock’s chaotic abstractions, Picasso’s disturbing Guernica, or a gorgeous Monet water lily.

At a moment when so much of our social fabric has been casually torn apart by public health authorities, art is a vital activity of connecting to another human mind. As Tolstoy puts it in What Is Art?, “To evoke in oneself a feeling one has once experienced, and [then] . . . to transmit that feeling that others may experience the same feeling—this is the activity of art.” Or, as Mark Rothko stated, “the people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.” Art is also a public health intervention at a time when our physical health is seemingly at the forefront of everyone’s mind.

I lament that it has taken a once-in-a-lifetime crisis to clarify these beliefs for me, although, my lamentations are lessened by the knowledge that one purpose of crises is to help us recognize what we truly value. All around me, I see people reaching their own conclusions about their own deeply held values. Some of these conclusions seem sensible and laudatory, and others seem incomprehensible and deeply disturbing.

Article found at lithub.com

Tuesday, October 6, 2020

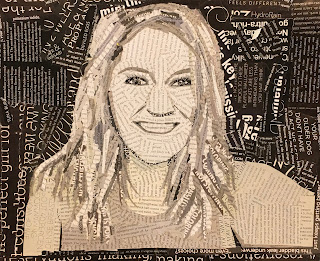

2020 Student Annual Show

This spring, the students at Benedictine University entered work from their art and graphic design courses for the 2020 student annual competition. Unfortunately, the school shifted to virtual instruction at the time the exhibbit was supposed to open. I have posted a sampling of works by some of the entrants. As you can see they are a very talented group of students. Many thanks to all the participants, the art and graphic design instructors and you the public.

Labels:

graphic design,

lettering,

photography,

Printmaking

Friday, January 3, 2020

Festival of Trees III - Ringing in the Holidays

The Komechak Art Gallery recently celebrated its third annual Festival of Trees exhibit. In addition to the lovely variety of custom decorated Christmas trees, this year's display included dozens of creche sets on loan from Marmion Academy, as well as creche sets from the university's permanent art collection.

This exhibition utilizes the assistance of community volunteers, university staff, faculty, special interest student groups, area high schools and holiday donations from the community. The coordination of all these workers is daunting, but deftly organized by Mrs. Cathaleen Gaddis, who is the Assistant to the Curator at the Komechak Art Gallery. Below are some pictures from this year's display. Enjoy! For more information regarding the spring 2020 exhibitions and programs, go visit the art gallery's website at www.ben.edu/artgallery

Labels:

Christmas trees,

creches,

Festival of Trees,

Marmion Academy

Saturday, October 5, 2019

"Town and Country" by Douglas C. Johnson

The paintings of Douglas C. Johnson represent a singular vision of the beauty of Nature, and the simplicity of small town America. His landscapes and small town scenes are taken from central Illinois. The views he presents to us are those moments in time where we stop what we are doing and take a breath while we look at Nature and reflect on the elegance of a field of ripening corn, the pillows of clouds rolling across the sky, and the warmth of a sunset upon a building, putting everything in an orange glow.

Johnson's paintings harken back to works of Hopper's small towns of quietude and even Monet's cool sunrise mist. He transcends anyplace to make these scenes a place we all know, or at least we want to be familiar with them. His choice to portray singular places or fields captures our attention and lets us take time away from our busy lives to enjoy reflections on a pond, or a n old diner by the side of the road. There are numerous places Johnson has found that speak to one's soul and need for solace in Nature.

His recent "Town and Country" exhibit at the Komechak Art Gallery is a terrific group of works and they show his prowess and accomplishment of the subject. The exhibition runs October 1 through November 2, 2019.

Education

MFA, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois 1992.

MS, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois 1991.

BFA, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois 1987.

Teaching Experience

Judson College, Elgin, Illinois. 1995-1997.

Waubonsee College, Sugar Grove, Illinois. 1993-1995.

Illinois Art Institute (Ray College of Design), Chicago, Illinois. 1992-1993.

Rockford Art Museum, Rockford, Illinois. 1992-1993.

Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois. 1990-1992.

Professional Memberships

Arts Alliance Illinois. Board Member- 2011 to present

College Art Association, 1990-Present

Wednesday, September 18, 2019

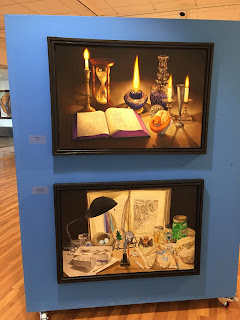

The Surreal and Super Real Paintings of Yale Factor

The recent painting exhibition of noted artist Yale Factor brought a mixture of landscape and still-life pieces that dazzled the viewers and made us want to see more. Factor has been a realist painter for decades, and with that experience he portrays a vision of the world we feel is somehow overlooked by the average person. In essence, he finds the one spot of landscape that is particularly more interesting than the rest of it. He shows us the one spot that we should not miss, otherwise we have missed everything.

There is an inner glow to his landscapes. His linear details are extraordinary and they call us to the canvas and leave us in awe of his talent.

Factor's still-lifes are intriguing on their own level. His homage to the subject of still-life painting is apparent. The subjects are sometimes playful, sometimes poignant, but they are carefully considered items in the compositions that lend themselves to invention of stories and adventures. When Factor tells the story of one of these gems, we feel as though we have been given the keys to a well-veiled secret. All in all, these are works by a master who is at the top of his game. The exhibition continues through September 21st.

Education:

MFA Texas A & M University, Commerce, TX

BFA Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL

Experience:

Professor Emeritus, Northern Illinois University, Dakalb, IL

Scientific Illustrator, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL

Wednesday, June 26, 2019

Remembering Fr. Joe Kelchak

Benedictine University has been blessed with donations of art over the last few decades. So much so that when the university was finally able to open its first official art gallery in 2013, named the Komechak Art Gallery, the opening exhibition featured a number of works by various donors. It was a celebration of many supporters for the gallery, but also for the donors who have been generous to share their collections with the Benedictine community.

One of those donors was The Very Reverend Joseph Kelchak, or Fr. Joe, as he was often called. His legacy to the university was his wide-ranging and eclectic art collection which spanned many subjects, media, and styles. Eventually, Fr. Joe's donations would become so numerous that he became the art collection's largest donor. When one visits the campus at Benedictine University, they can see works from his donations in virtually every building. The Komechak Art gallery is proud to display a sampling of Fr. Joe's collection (from June 1 - July 20, 2019) in celebration of his many contributions.

The exhibition features works donated in recent years, including paintings, prints, sculptures, and ceramics. As a global art collector, Fr. Joe's vision included religious works as well and contemporary art from Europe, Israel, Mexico, Africa, the South Pacific rim, Native American works and artists from the United States. Some notable names from his donations include Henri Matisse, Gino Severini, Georges Rouault, Maurice Utrillo, Robin Branham and many others.

One of the first persons to call me as the new curator of the university collection was Fr. Joe. He introduced himself and explained that he was a close friend of my predesessor, Fr. Michael Komechak. Fr. Joe told me what he'd recently donated, and then proceeded to tell me all about the pieces. Whenever I visited his home, he would take me around and introduce me to his collection. He was very excited about it and loved relating stories about how he acquired the pieces, and from whom. It was always a treat to go to his home to see what was added to his collection, and see how he arranged it to best advantage. Those afternoons were a delight, and will remain fond memories.

Below are some more selected images from the current exhibition. If you are able to attend, the gallery's summer hours are M-TH 11:00 a.m.-3:00 p.m. The gallery's 2019-2020 schedule is found at www.ben.edu/artgallery.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)